Amongst the masterpieces of furniture in the Wallace Collection are ten works by Jean-Henri Riesener (1736–1806), the celebrated eighteenth-century royal cabinetmaker. All ten were bought in the middle of the nineteenth century by Richard Seymour-Conway, the 4th Marquess of Hertford (1800–1870).

Lord Hertford was brought up in France and England in the glittering interiors of Restoration Paris and Regency London, where the sumptuous Anglo-Gallic taste dominated fashionable interiors.

From 1829 he chose to live in Paris, buying a large apartment at no. 2 rue Laffitte, on the corner of the boulevard des Italiens and six years later bought Bagatelle, a small pleasure house that had been built for the comte d’Artois, later Charles X of France, in 1777. Apart from a few absences, he chose to spend the rest of his life in Paris.

In 1840 his father died and he inherited an estate of some £2 million, a vast sum. From this time on he was able to indulge his life’s passion for art collecting. His taste was as much French as English and, alongside Old Master paintings, he favoured paintings and decorative art from the French 18th century. The finest examples of cabinetmaking were complemented by a superb collection of Sèvres porcelain, gilt-bronze clocks and furnishing bronzes, such as candelabra, candlesticks and firedogs.

Closer Details

Please drag left or right to browse the gallery and click on an object to expand it.

Works by Riesener were increasingly sought after by collectors during the middle decades of the nineteenth century, and Hertford was at the forefront of driving this taste. At his death in 1870 he owned at least twenty pieces either by Riesener or in the Riesener style.

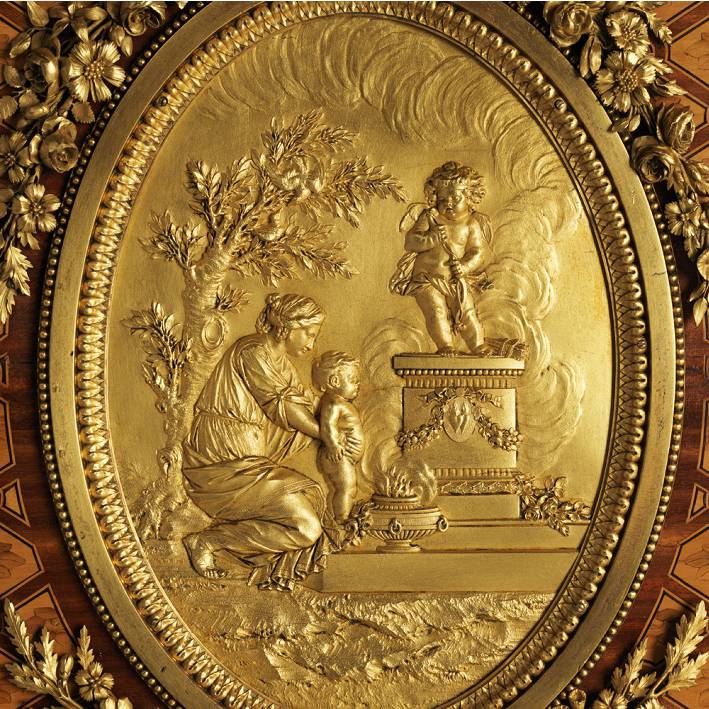

Several factors combined to make Riesener’s work appeal to Hertford: not only were they superbly executed and of the highest standards of craftsmanship, but they were also adorned with some of the most beautiful gilt-bronze decorative mounts ever made. Additionally, Hertford liked the connection of Riesener to the court of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette, for whom much of his furniture had originally been made.

A Closer Look at Riesener

Please drag left or right to browse the gallery and click on an object to expand it.

A MARKET FOR RIESENER

As the market for Riesener became heated, dealers and auctioneers increasingly used his name and his connection with the ancien régime as a way to sell furniture, whether by him or not. Sometimes stories were invented about a piece, or alterations made to appeal more to nineteenth-century buyers, and in some instances fake marks were added.

Despite his knowledge and connoisseurship, even Hertford was not always able to avoid buying furniture that had been altered or even made up. Some of these changes had been carried out long before he started buying, such as the mahogany veneer that had been added to one of Marie-Antoinette’s chest of drawers, or the gilt-bronze medallion that had been mounted onto a fall-front desk.

In one instance, at the end of his life, Hertford bought a pair of corner cupboards at auction that were described as having come from Marie-Antoinette’s elegant hideaway, the Petit Trianon, when in fact only one of them had been made for the queen and the other had been made up to match it sometime in the nineteenth century.

Not all copies were fakes. Such was the interest in eighteenth-century furniture and, increasingly, the nostalgia for the luxurious interiors of the ancien régime, that copies of original pieces were commissioned so as to be able to recreate the look of the past century.

Lord Hertford was the first major collector to commission copies of great works by Riesener, a fashion which he started and which was to become almost mainstream by the end of the nineteenth century.

The most famous and most expensive copy he commissioned was in the mid-1850s, the copy of the bureau du Roi, or King’s Desk, that had been made by Riesener for Louis XV. The original King’s Desk was displayed by Empress Eugénie in her apartments at the Palace of Saint-Cloud, and since Hertford was a friend of the imperial couple it is here that he would have seen it.

Queen Victoria used the room as her sitting room on a state visit to Paris in 1855 and wrote at the desk. The copy of the King’s Desk was made in Paris and apparently cost Hertford the equivalent of £3,000, an enormous sum at that time.

A JEWEL CABINET COPY

In London, Hertford had copied the spectacular mahogany-veneered jewel cabinet that had been made by Riesener in 1787 for Marie-Antoinette’s sister-in-law, the comtesse de Provence. It was owned in the nineteenth century by Queen Victoria, so Hertford knew that he would never have been able to buy the original.

The jewel cabinet copy cost £2,500 so it is clear from the prices that these copies were highly regarded as works of art in their own right. There was none of the snobbery associated with copies that started to make itself felt towards the end of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. In fact, Lord Hertford so admired the work of contemporary cabinetmakers and bronze workers that he had a total of fourteen more copies of celebrated pieces of French furniture made in London and Paris.

Alongside exact copies, French cabinetmakers produced furniture in the Riesener style, for example the firms of Wassmus, Grohé Frères and Winckelsen, and Hertford owned pieces in this genre too.

By the end of the nineteenth century, reproductions and pastiches of Riesener furniture were mainstream and furnished fashionable interiors in Europe and the US. Major firms like Beurdeley, Dasson and Linke continued to produce high quality pieces, but the novelty and superlative design of Riesener’s original works were never surpassed.