Venetian glass in the Wallace Collection in context

Venetian and façon de Venise glass in the Wallace Collection

The Wallace Collection is home to nearly fifty pieces of Venetian and Venetian-style (façon de Venise) glass. Most, if not all of them were acquired by Sir Richard Wallace in August 1871. Ranging in date over more than 200 years, from around 1500 to the early eighteenth century, they testify to the enduring success of Venetian glass.

Its popularity meant that Venetian-style glass was produced elsewhere contemporaneously for much of this period, but attempting to distinguish Venetian from façon de Venise examples was not a serious preoccupation in the nineteenth century, and pieces were usually described as Venetian.

The nineteenth-century revival of Venetian glass production

The popularity of Venetian glass had greatly diminished by the late eighteenth century, due to a combination of factors. The taste for the highly malleable soda-lime-silica glass that enabled the production of the audacious wares produced in Venice began to give way in the later seventeenth century to a vogue for heavier, thicker potash or lead glass associated with Bohemian and English glassmaking. One manifestation of this change of taste was the early nineteenth century fashion for the deeply facet-cut lead crystal table wares so popular in Regency England. The demise of Venetian glassmaking was also exacerbated by the fall of the Venetian Republic in 1797 and the city’s economic decline.

Yet by the mid-nineteenth century interest in and appreciation for historic Venetian glass, and the desire to take inspiration from it to reinvigorate the industry in Venice, was growing at a prodigious rate. This was in part due to a more widespread increased interest in the historic past. In France, for example, in the wake of the French Revolution, one manifestation of this interest was the development of the revivalist Troubadour style. In Venice, the revival of the glass industry was also motivated by Venetian pride and self-identity.

The revival of the Venetian glassmaking industry in the third quarter of the nineteenth century was like the rising of a phoenix from the ashes. A key figure in its revival was Abbot Vincenzo Zanetti, who was instrumental in establishing, on the traditional glass-making island of Murano, the Murano Glass Museum in 1861 and the neighbouring school for glassworkers in 1862.

Undoubtedly the best-known name associated with nineteenth-century Venetian glassmaking is that of Antonio Salviati, who founded several companies after becoming involved with the revival of the glass industry in 1859. In 1866, the year in which the Veneto was annexed to the Kingdom of Italy, Salviati opened a blown glass factory, Salviati & C., with the help of British funding. Its name changed in 1872 to The Venice & Murano Glass & Mosaic Company Limited (Salviati & C.). In 1877 he founded Salviati & Compagnia for mosaics and Salviati Dr. Antonio for blown glass. Salviati’s vessel glass took its inspiration from historic precedents, which were creatively reinterpreted to produce light, fanciful and audacious pieces with a modern aesthetic.

Contemporary Venetian glass reached a wide audience through the international exhibitions that had been initiated by the Great Exhibition in London’s Crystal Palace in 1851. Held intermittently in succeeding decades, they acted as a stimulus for improvement in industrial design and provided a forum in which manufacturers could display their products to a wide audience. Products shown at the exhibitions could benefit from wider exposure through related press coverage. The range of publications featuring exhibitions and the arts more widely, from newspapers to specialist journals and lavishly illustrated volumes, increased significantly in the latter half of the nineteenth century.

Collecting historic Venetian glass in the later nineteenth century

The resurgence of glassmaking in Venice developed in parallel with the acceleration of collectors’ interest in historic Venetian glass. In England, the public’s attention was initially drawn to it in the 1850s, with the sale of Ralph Bernal’s art collection at Christie’s in 1855, and the inclusion of many examples at the Art Treasures of the United Kingdom exhibition held in Manchester in 1857. However, it was in the 1860s that collectors’ enthusiasm for historic Venetian glass of the so-called ‘Golden Age’ — from the mid-fifteenth century to the seventeenth century — increased exponentially.

The interest of French and British collectors would have been piqued by articles on the history of Venetian glass published in Paris in 1861. The rapidly growing interest in the subject is reflected in the more than sixty examples shown in the Special Loan Exhibition held at the South Kensington Museum in London in 1862 and the almost two hundred pieces included in the Musée rétrospectif exhibition in Paris in 1865. In France, 1863 saw the publication of the lavishly illustrated catalogue of the Sauvageot collection of Renaissance works of art which the eponymous collector had presented to the Louvre in 1856. This included a superb assemblage of Venetian glasses. William Holman Hunt’s Portrait of Fanny Holman Hunt, painted in 1866, bears witness to this enthusiasm. A colourless glass bowl, closely comparable to an example in the Wallace Collection (C515), is displayed on the mantlepiece behind the artist’s wife.

Perhaps the world’s greatest collection of ‘Golden Age’ Venetian and façon de Venise glass is in the British Museum. Its outstanding collection is due mainly to the bequest it received from the collector Felix Slade in 1866–8.

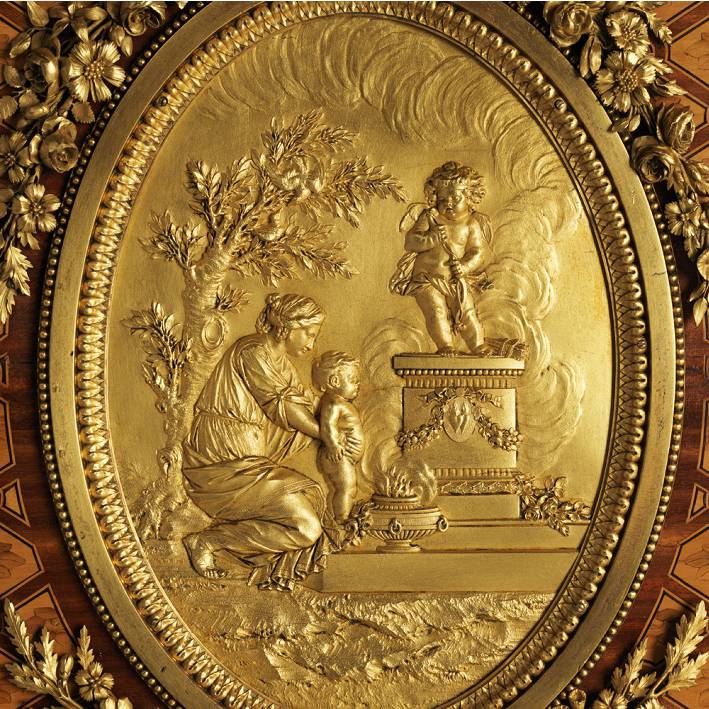

It was also during the later 1860s that many of the glasses now in the Wallace Collection were acquired in Paris by Alfred-Émilien O’Hara, comte de Nieuwerkerke. As surintendant des beaux-arts, Nieuwerkerke was the pivotal figure in the official art world in Second Empire France. He assembled a large collection of medieval and Renaissance works of art and arms and armour.

A Closer Look

Please drag left or right to browse the gallery and click on an object to expand it.

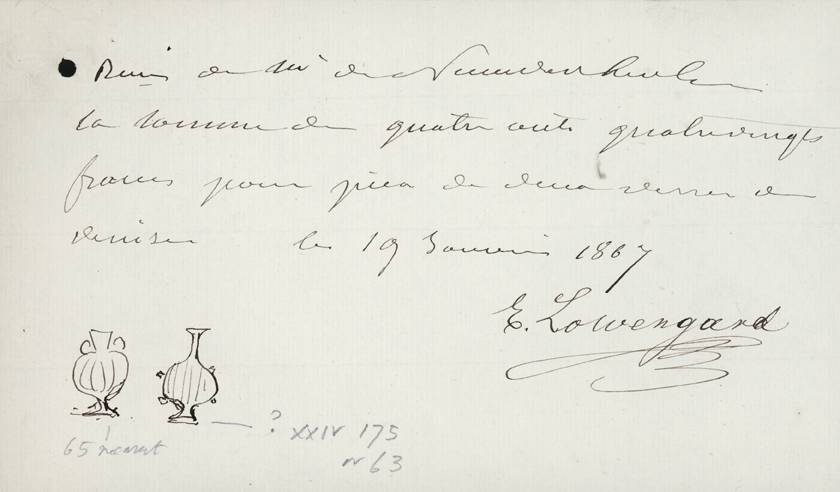

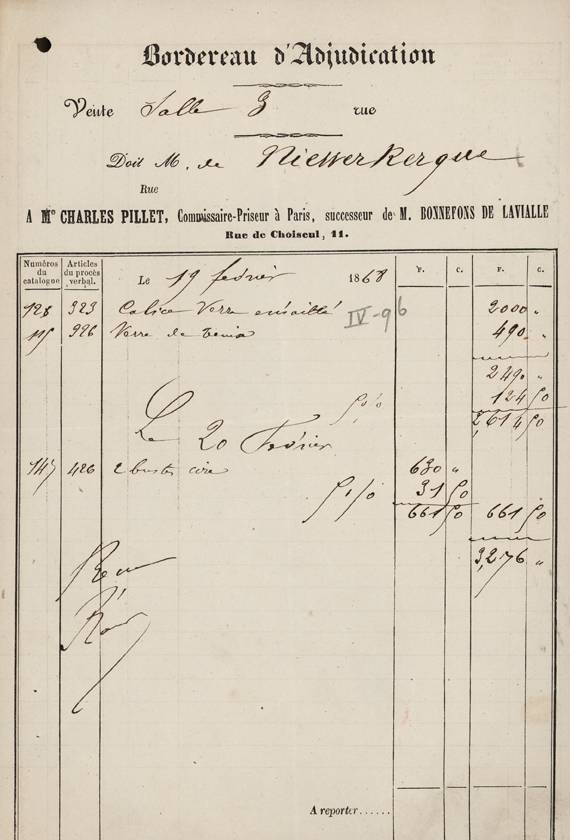

Following the fall of the Second Empire, Nieuwerkerke was obliged to sell his collection in 1871. He was fortunate to sell it en bloc in August 1871 to Sir Richard Wallace, who had recently come into a substantial inheritance form the 4th Marquess of Hertford, his likely father. The receipts for his purchases that Nieuwerkerke gave to Wallace with the collection enable a number of the glasses in the Wallace Collection to be identified as having been bought by Nieuwerkerke when collectors’ taste for Venetian glass of the ‘Golden Age’ was at its apogee.

Suzanne Higgott, Curator of Glass, Limoges Painted Enamels, Earthenware and Early Furniture