Date: about 1785

Maker: Cabinetwork attributed to Jean-Henri Riesener

Materials: Oak, conifer, mahogany, gilt bronze, Carrara marble

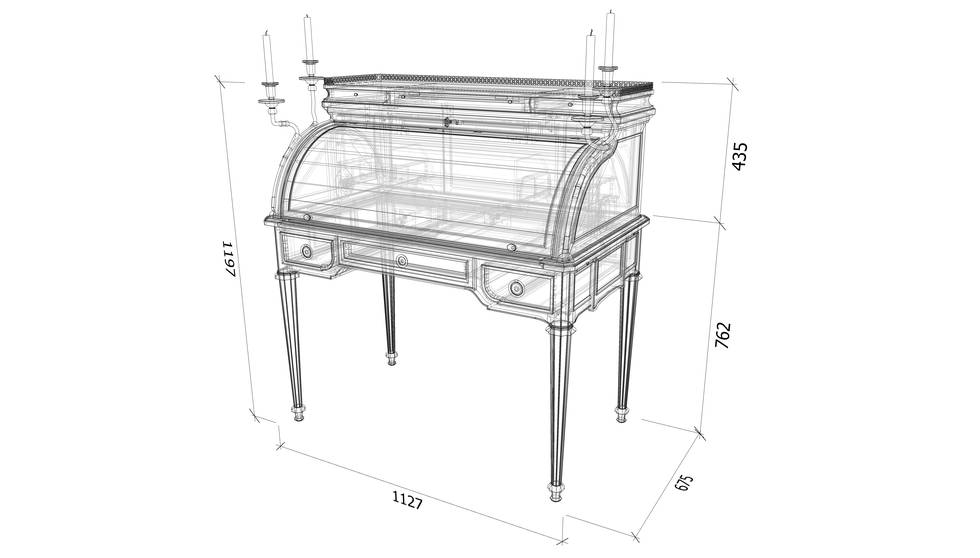

Measurements: 124.2 x 121.5 x 68 cm

Inv. no. F277

After the delivery of the King’s Desk to Louis XV in 1769, Riesener’s reputation was made and his future success secured. The roll-top desk as a form was not invented by Riesener, although his master, Oeben, seems to have delivered one of the earliest of this type, but it became almost his signature piece, with many members of the royal family and their household ordering one for themselves. This included Louis XVI’s brother, the comte de Provence and his wife, and several of Louis XVI’s aunts.

Although only one of his subsequent desks was on the scale and complexity of the King’s Desk, Riesener cleverly adapted the concept of a roll-top, or a cylinder-top (where the top is one surface, rather than slatted), in a variety of ways that made each desk different. Sometimes this difference was in the marquetry decoration and the mounts, sometimes in the interior, and sometimes it was in the materials used.

By the early 1780s, the fashion for mahogany furniture had taken hold in Paris. This is somewhat later than in England, where there had been a good supply of the timber for many decades, and it was a fashion in keeping with the ‘anglomania’ that affected dress, sport and garden design, amongst other things.

While royal cabinetmaker, Riesener had from time to time supplied the royal household with mahogany items, but generally the furniture for members of the royal family had been veneered with his characteristic marquetry. In 1784, he was commissioned to make at least five mahogany cylinder desks for members of the court, including one for Thierry de Ville-d’Avray, the new head of the royal furniture administration.

It has not been discovered who this desk was made for, but it dates to around that time. Its relative simplicity belies the complexity of the engineering and the quality of the materials, since the mahogany veneer is of the highest value and has been chosen for the decorative effect it makes; now faded, its colour would once have been much richer and the ‘flame’ effect more pronounced.

Riesener has used many aspects of his customary designs, including the ‘breakfront’ feature of the sides and back, in which the central panel stands proud from the sides (a feature of the fronts of many of his chests-of-drawers); the octagonal legs with each side alternatively flat and concave, separated by gilt-bronze mouldings; and several of the gilt-bronze mounts. What is unusual are the candle branches springing from either side of the desk, with their rope and tassel arms beautifully chased in gilt bronze.

The King’s Desk, almost twenty years earlier, also had candles sconces although of a much more sculpted nature, and from a practical view it would have been a very sensible design feature as candles were the only form of artificial light in a room and must have been required for much desk activity.

When the top is pushed back, a writing slide can be pulled forward. In addition, two other slides can be pulled out, one from either side of the desk. These would have allowed a secretary to take notes, or could have provided extra space on which to lay out papers.

An inner cabinet has the customary Riesener mixture of shelves and drawers, and underneath the writing surface there are three more drawers. As an extra feature, there is a thin platform above the cylinder and below the marble which conceals two more slim drawers and a book rest for reading. This is pulled out like a drawer, and then the surface can be angled to allow a book to be placed on it. In the contemporary descriptions of this feature, it was explained that it was to allow someone to read while standing up.

One of the aspects of Riesener’s working practice was the way in which he standardised many of his models to allow him to repeat them, since once the plans were developed the subsequent versions would have been less expensive and quicker to produce. In 1786, Marie-Antoinette ordered a cylinder desk from Riesener for her private apartments at the Château de Fontainebleau.

This was an extraordinary feat of cabinetmaking as it was decorated with lozenges of mother-of-pearl. The measurements of that desk, and the essential form, correspond very closely with the mahogany-veneered desk here, which probably dates from around the same time or maybe a little earlier and which is likely to have shared the same working drawings.

For more information: Jacobsen, H. et al., Jean-Henri Riesener. Cabinetmaker to Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette. Furniture in the Wallace Collection, Royal Collection and Waddesdon Manor, London, 2020, no. 26.